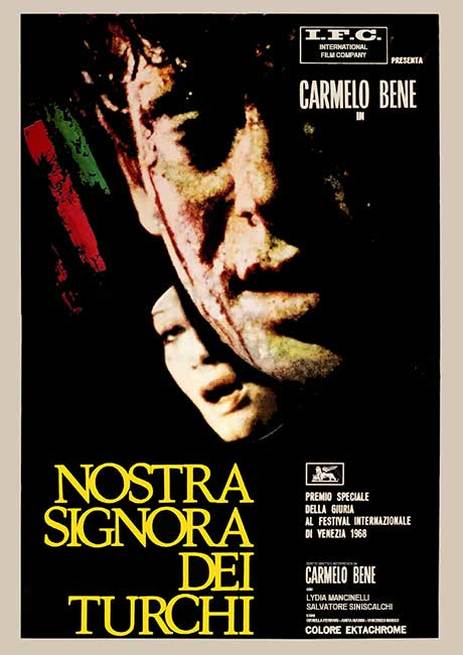

Director: Carmelo Bene

Screenplay: Carmelo Bene

Cast: Carmelo Bene as The Man / Narrator; Lydia

Mancinelli as Saint Margareth; Salvatore Siniscalchi as The Publisher; Anita

Masini as Holy Mary / The Woman

[Plot Details and Spoilers]

All careers begin somewhere, and

the cinematic debut of Carmelo Bene as

director was here. I had thought to my surprise, in lieu to his future

trademark of hyper-exaggerated acting and artificially rich environments, of

how subdued the prologue is. This will change, but Our Lady of the Turks for a large portion of its length is a calmer

production, beginning with the narrator (Bene

himself) elaborating the tale of the Martyrs of Otranto, inhabitants of the

Salentine city of Otranto in southern Italy who were killed on 14th August 1480

by an invading Ottoman force who took the city, described here as being

massacred as they refused to convert from their Christianity to Islam. From

here, Bene builds to a delirium very

common to his other work but with a different tact.

All careers begin somewhere, and

the cinematic debut of Carmelo Bene as

director was here. I had thought to my surprise, in lieu to his future

trademark of hyper-exaggerated acting and artificially rich environments, of

how subdued the prologue is. This will change, but Our Lady of the Turks for a large portion of its length is a calmer

production, beginning with the narrator (Bene

himself) elaborating the tale of the Martyrs of Otranto, inhabitants of the

Salentine city of Otranto in southern Italy who were killed on 14th August 1480

by an invading Ottoman force who took the city, described here as being

massacred as they refused to convert from their Christianity to Islam. From

here, Bene builds to a delirium very

common to his other work but with a different tact.

In this context provided by his

voice over, Bene plays a nameless

man, a personification of a figure whose bones are part of their surviving

form, the Cathedral of Otranto having the bones of the martyrs built into an

alter of skulls in their memory, Bene

a man who prayed to the Madonna during the Ottoman force's attack. In this form

however, said man is now a figure who wanders both the landscape and between

time, in the modern day region of Apulia, Italy and in the past including as a

knight. Bene has used real locations

later, but it is a jolt to see him use far more naturally decorated locations,

including the startling sight of the Alter of Otranto housing those skulls, and

environments whose natural lightning and form are a vast contrast to the

sensitory overloading stages of films into the seventies like Salome (1972).

The pace is also more subdued for

a long time, taking its time to escalate as, in the midst of his aimlessness,

the Man has rejected his initial faith and is even trying to flee the Madonna

he once beckoned to, something which is proven difficult for him as he manages

to court the influence of the of the female saint Santa Margherita (Lydia Mancinelli), who is there under

the presumption that under her (wire) wings and halo he can become a noble

figure. Plot wise, it is a film of tangents, including a period of trying to

publish the writings he made of her to a publisher and being stricken by an

illness which proves a hindrance to Margherita's desire (and romantic interest)

in this lowly mortal and his holiness. Eventually, finding a way with her

influence to effectively get his leg over with a woman, proves the breaking

point for her in this relationship.

It is a difficult film eventually

to grasp, at least within one viewing, as it shudders into tangents and

extremes. Our Lady of the Turks even

passes into territory with Bene

playing Carmelo Bene, at least

evoking the real man as audio of an interview is eventually heard about his

relationship with cinema and desire to break from Italian neo-realists like Roberto Rossellini. Reality is disrupted

anywhere between his sleep being intruded upon when his bed is unexpectedly

near pedestrians and a passing car, or when (using a very grotty stove) he

looks like he is injecting heroin (or something) into a buttock in the middle

of the outdoor area at a cafe. He even hunts down and shoots himself in one of

the first scenes of the film after the prologue, imagery which can be

interpreted many ways but could be seen the fragments of this figure, clearly a

soul lost in purgatory as his remains are in the Altar of Otranto, stuck in the

scenario of not wanting Santa Margherita to follow him but that, if she leaves,

he will die fully and she will not be allowed by up-above to resurrect him.

If there is any coherent through

line to what any of this means, one monologue does grow in hindsight, where Bene in voiceover talks of how rarely

people see the Madonna, that "idiots" who see the Madonna become her,

a madness which brings them to a saintliness inside themselves, whilst those

"idiots" who do not wander from alter to alter, to people and women,

trying to find her, possible to get to Heaven but (as perfectly used as a

metaphor) like dragging oneself to the gates with one's feet amputated, the

onlookers looking on at the blood trail behind oneself and realising that will

eventually prevent a person from getting there. Religious faith is, truthfully,

a subjective thing and, if one believes in Gods, a very unpredictable thing

which does not come to one's disposal at a beck and call at a moment's notice,

not even needing to be more than a subtle change of mood anyway and not

requiring a burning bush unless to get the message across in very significant

situations.

In his character's rejection of

Catholicism and his roots, and knowing the director-writer-star is Italian, a

Roman Catholic country, I cannot help but see the one clear plot thread in this

having a greater weight, the utter difficulty of raising oneself to a holistic

good or a holistic virtue an issue, even if he was not rejecting it, found in

how the Man succumbs to temptations and dicking about to a Saint's

frustrations. Ironically, at the moment when he rejects her, the Man finds the

Madonna, and she is not a vague figure constructed from puritanical

objectification either. She is not perfect, hinting that she was not a perfect

person even in Heaven but getting sainthood still means she at least earned it,

a sympathetic and beautiful figure with her homemade (theatrical stage) prop

halo and wings who is disappointed that her knight figure. Whilst it might have

been a blasphemous scene on purpose, the moment she first appears it is very

much implied Santa Margherita sleeps with him, the next morning undressed in

his bed baring her halo reading a fashion magazine and smoking. It also offers

something sweet in itself, a Saint who is still human, still has desires and is

depressed when he is eyeing another woman instead, but still earned the halo.

It is to the point she has

decided to tow along with this shambolic "jerk", even taking a boat

and rowing it for him as they travel over the sea, only to have the Man find an

excuse to merely shag a woman, a homely earthy figure with infant who is just

an innocent bystander in his madness and not villainized either. In fact, the

earthy description is more than apt, she is literally shot bare breasted as a

figure of Mother Nature at one point in a disorientation close up from inside

the soil upwards, a figure of beauty too. Literally, at one point he is the

knight, his soul trapped in the bones preserved as decorations in the Altar of Otranto,

just wanting that same woman to release him, to bury his bones, but that is

just a ploy to seduce her.

The sequence that shows the

breaking point for this character of the Man, and how far he has gone, capable

of some humanity but also lost permanently, is also evidence of how good Carmelo Bene in terms of his performance

and sustaining such a hyper intense acting style, when he eventually becomes

two people briefly, an older monk and a younger one, not depicted in

duplication technique but Bene acting

out both by himself, occasionally with a fake beard to differentiate the two.

Acting like this is not giving as much deserved respect as it should be, as to even

perform at this level of intensity regardless of the type of film would be

difficult and a strain physically. It is a frenzy onscreen here, this character

reduced to a gibbering idiot, between a cruel and older figure who lashes out

at the other and that younger monk who squeals in pain between the pair trying

to eat. By this point, the aesthetic from its naturalistic locations has

aspects that are utterly grotesque and grim, the least sanitary cooking stove

in any film at least witnessed here, whilst Bene

shows both an incredible way of cracking an egg on his own head, without

looking the yolk, only to start eating it raw when his monk character is meant

to be making an omelette. It is a cacophonous sequence, played by only one man

who sparks with a thunderous, scary energy.

The production has a heavier

reliance on real life locations - in the middle of the day in idyllic locations

no less too - which changes Our Lady of the Turks from Carmelo Bene's later films. Those later productions had a

tremendous visual palette but an artificial one, the aforementioned Salome even predating eighties

underground films like Dr. Caligari

(1989) for neon colours, or One

Hamlet Less (1973) being a work of elaborate costume and visual work. The

greater emphasis here on naturalistic and ornate set design is a striking

change, especially as Bene eventually

shifts the tone to a far more grimier and gothic tone, even himself

transforming at one point in a revenant like figure with eyes rolled back into

the head and affecting a cavernous voice. It lives up to his intensity still,

and you will eventually find one lost in the delirium, but the change in

aesthetic allows this film to have uniqueness among his filmography.

Out of all of them, Bene's debut was successful in terms of

that, at the 1968 Venice Film Festival, Our

Lady of the Turks won the Special Jury Prize, sharing it with the Robert Lapoujade film Le Socrate (1968). The Special Jury

Prize is just below the main Golden Lion that was won by another director not

easily available as he probably should be, West German figure Alexander Kluge for a collage structured

film about circus performers Artists

Under the Big Top: Perplexed (1968), which I openly confess to have never

have heard of before researching this. Considering the competition had Pier Paolo Pasolini's Teorema (1968), who Bene would be cast in his 1967

adaptation of Oedipus Rex, and John Cassavetes' Faces (1968), that was a pretty big success for Bene to have accomplished1.

It's worth mentioned Amos Vogel's Film as Subversive Art (1974),

as if anything is partially responsible for these reviews, that and all the

podcasts and tomes championing cult cinema made an impact for myself in

combination with Vogel's championing

of subversive and unique productions. Seeing the image of Bene in the book, as that almost undead figure with the pupil-less

eyes, I did not realised that, in a bizarre future, I would be watching this

unique film on Amazon Prime streaming, but the aura around this film has

thankfully become even stronger as a result of actually seeing this. It lives

up to that initial discovery, the text review of the book I found in the

university library, and a reminder of this very different era of cinema of the

sixties and seventies that Carmelo Bene

existed in. He could be able to create an almost improvised, stream-of-consciousness

like tale like this with this level of theatricality. It is apt to talk of his

career from the first film as, by the late seventies to the end of his life, he

would be mostly filming TV movies and documentaries after a fever dream of

films to 19732. He started here perfectly, with Our Lady of the Turks, and Bene

would not disappoint after his initial success either.

Abstract Spectrum: Avant-Garde/Delirious/Intense/Surreal

Abstract Rating (High/Medium/Low/None): Medium

===

1) Whilst IMDB is not always

reliable, their source as of 10th May 2020 [HERE] also had Maurice Pialat's first theatrical film L'Enfance Nue (1968), D.A. Pennebaker's concert film Monterey Pop (1968), and films by Miklós Jancsó and Juraj Jakubisko among those screening. Time has made other films

more acclaimed since the decades have passed, but it's fascinating in itself to

see such idiosyncratic productions jostled together like this, causing one to

wonder how in the future Cannes and Venice Film Festival premieres of the 2000s

and 2010s will be seen.

2) All, having yet to see Capricci (1970), deserving a box set

that both art house and cult cinema fans would by enraptured by.

No comments:

Post a Comment