|

| From http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-dtldVAg9LIM/U-Dyf0I94LI/ AAAAAAAAGtU/XSoAKAER1WM/s1600/jaqHR.jpeg |

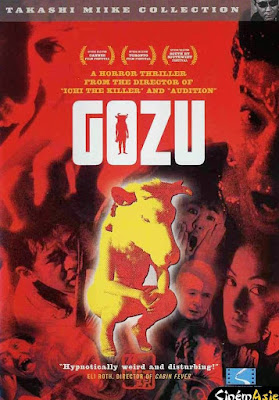

Director: Takashi Miike

Screenplay: Sakichi Satô

Cast: Yûta Sone (as Minami); Shô

Aikawa (as Ozaki); Kimika Yoshino (as Ozaki); Shôhei Hino (as Nose); Keiko

Tomita (as the Innkeeper); Harumi Sone (as the Innkeeper's Brother); Renji

Ishibashi (as Minami's Boss)

Synopsis: When his mentor and senior yakuza Ozaki (Shô Aikawa) is deemed to have lost his competency

and sanity, requiring "disposal", the younger gangster Minami (Yûta Sone) is the one forced to take him

away by his seniors only for Ozaki to both die accidentally and for the body to

vanish in broad daylight from his car. Stuck in a small town trying to find his

mentor, Minami's investigation leads to a mounting series of bizarre people and

events, stuck in an inn where the owners are strange and more than happy to

provide twice a person's worth of food, stuck in a small town where he's seen

as a foreign body and going around in circles in spite of the assistance of the

partially white faced Nose (Shôhei Hino)

to find Ozaki. Then there's a beautiful woman (Kimika Yoshino) claiming to be Ozaki and can manage to actually

prove who she is.

Synopsis: When his mentor and senior yakuza Ozaki (Shô Aikawa) is deemed to have lost his competency

and sanity, requiring "disposal", the younger gangster Minami (Yûta Sone) is the one forced to take him

away by his seniors only for Ozaki to both die accidentally and for the body to

vanish in broad daylight from his car. Stuck in a small town trying to find his

mentor, Minami's investigation leads to a mounting series of bizarre people and

events, stuck in an inn where the owners are strange and more than happy to

provide twice a person's worth of food, stuck in a small town where he's seen

as a foreign body and going around in circles in spite of the assistance of the

partially white faced Nose (Shôhei Hino)

to find Ozaki. Then there's a beautiful woman (Kimika Yoshino) claiming to be Ozaki and can manage to actually

prove who she is.

Gozu is an episodic odyssey with

a nod to Alice in Wonderland, not in

presentation but the idea of a person finding themselves wandering in a strange

place with bafflement at everything they witness. Admittedly the film does start strangely

already. Miike's almost interpreting

what a David Lynch film is like with

Minami watching a television is a cafe with his gang which is entirely

distorted and about someone wanting to lactate but isn't being allowed to, a

stiltedness to the initial performances and scored, as throughout the film when

it isn't completely silent, but ominous strings by perfectly implemented by Kôji

Endô. Ozaki, played by Shô Aikawa,

immediately sets the bar by randomly killing a small dog outside in front of

two terrified women, having claimed its a yakuza attack animal and proving he's

lost his marbles, setting up the black humour immediately off the bat. However this

is sane for Miike, his usual balance

between seriousness, that has a surprising amount of cinema verité in the

grungy environments and minimal use of music, and bizarre punctures into

transgression and slapstick. Gozu

actually has a visible shift for protagonist Minami where he'll enter his

Wonderland, reaching a road in his car that's completely swallowed up ahead by

a river, a sudden glitch in the image and distortion in the soundtrack, his

mentor inadvertedly dead before Minami finally developed the courage to kill

someone he had platonic and friendly love for. Than Ozaki's body vanishes when

trying to phone his seniors in a cafe and has to puke up an egg custard he's

didn't order in the bathroom.

|

| From http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-N1qmu9K05K4/U-DxH5oh-UI/AAAAAAAAGsU/ VwUnisTgLIU/s1600/vlcsnap-2014-08-05-20h13m35s97.png |

Technical Detail:

Yet Gozu, from this initial premise, emphasises one of Miike's best virtues especially from all

the films up to this one of the slow, deliberate tone. Miike even in some of his most notorious films usually paces his

work with a greatly leisured tone; ironically its now as a much older veteran,

making more mainstream films and adapting manga more so than before in his

early career, that he's making faster pace films rather than the presumption

older directors become more sedate. This slower pace helped him in even the

stranger genre works of his to always emphasis characterisation, here of

immense importance as its entirely down to the fresh faced Yûta Sone to anchor the film, playing a virginal adult yakuza lost

in a realm of sexual obsessions and various distractions he's forced to go

through which exasperation like a labyrinth of nonsense. The cast helps

greatly, full of regulars from Miike's career

in large and minor roles who, throughout all the films Miike made, are all talented actors able to bring an air of

seriousness even to the most ridiculous material. For example Renji Ishibashi, as the yakuza boss who

can only get an erection from an intricately inserted ladle, manages to give

this absurd character some gravitas so the character can be taken serious but,

helping this black comedy to succeed, is visibly having fun with the material,

as with everyone else in the cast recognisable or new to Miike's world here.

The slower, deliberate tone is

needed as its one of Miike's films

which is not inherently propelled by plot but a lot of character building, Minami's

search through the small town making up most of the film's length and deliberately

filled with pointless tangents, searching for clues which go in circles and arbitrary

goals to complete, even having to complete a riddle to get help from Nose (Shôhei Hino) in the first place, the

assistant of a local yakuza who's ability to be stroppy if angered is

tantamount and just as liable to delay Minami's quest. The lengthy running time

in hindsight of this isn't indulgent but a necessary, Gozu very much in the area of cinema and storytelling I love the

most of either dream logic or a journey which is not based on a quest, but a

small goal where like a sightseer the viewer and the protagonist(s) witness

things entirely new to them and have to respond to them. That this journey

becomes increasingly weird for Minami, who reacts with more and more shock and

alarm at everything he see, adds to the film and the slow burn pace allows for

each scene to be even more shocking for the viewer and hilarious. It helps in

being in Minami's place trying to rationalise the events around him, not only

the transgressive aspects like excessive lactation or a cow headed man in only

underpants appearing in his dreams, but the unexpected egg custard forced onto

him when he only orders coffee or how his outsider position to even his own

yakuza group makes him useless in convincing many he encounters into talking to

his straight about what he needs.

|

| From http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-em2Rm07_mqc/U00n7ac0DeI/ AAAAAAAADR4/YMHEBxB7Zdk/s1600/180ce618-0c96-c08a.jpg |

Abstract Spectrum: Mindbender/Surreal/Weird

Abstract Rating (High/Medium/Low/None): High

Undeniably, this is one of Miike's strangest films, a film where

character moments take up most of the time rather than a plot until the third

act where Kimika Yoshino comes in, rejecting

a rational beginning, middle and end for bookmarks side-by-side of increasingly

oddball events. It's known for its notorious sequences which stand out in the

director's career (the full adult birthing, Renji

Ishibashi's collection of ladles, the skin suits of yakuza tattoos

preserved in a freezer from all the disposed of yakuza) but the weirdness is

more palpable for how the film is grounded in tone in spite of its odd moments.

One of the biggest aspects to

this strangeness, in a career that's full of sexual issues and kink, is the subplot

of Minami's sexual yearnings, visibly in the plot to have feelings for his

mentor Ozaki. This is not the first relationship between gangsters that's

either yearning or explicit homosexuality shown in Miike's cinema, neither is it the first time this narrative plot

has taken place in a Miike film, Full Metal Yakuza (1997) leading to the

gangster who looks up to his stronger, wiser senior becoming stronger himself from

having his senior's body parts (including genitals) attached to his rebuilt

body. Here, it's a visible confusion in Minami's relationship with Ozaki, and it's

not through literal envelopment that this relationship is consecrated but with

a desire that's built up through flashbacks that suggest more is going on for

Minami, literalised when a beautiful woman appears who knows intimate secrets

about Minami that only his senior knew, claiming to be Ozaki herself and

breaking the wall Minami has had for his mentor. That this film is rife with

various forms of sexual kink brings to mind Gozu being entirely from the perspective of Minami's confused

sexuality manifesting itself in various forms.

But Gozu's success is truly found in how the normalcy is as much

strange as the more extreme content, maybe even stranger on subsequent viewings

when the initial shock of the more infamous scenes had faden. You're initially

struck by the odd sight of an older man in a gold tracksuit talking to a

similar one in a silver jumpsuit, only to find that their conversation about

the weather is one you'd hear in real life in an actual cafe and actually

strange in itself to realise. Sakichi

Sato, the screenwriter, also adapted Miike's

notorious Ichi the Killer (2001),

and alongside that film's deliberate complexity in its various transgressive

sexualities, it also had a huge emphasis even against other Miike films on

puncturing the extremity with bafflingly normal scenes and quiet gestures,

normal behaviour that feel alien in context of what happens around them even in

the same scenes. How the characters act or even one-off figures who don't

necessarily come off as wacky figures but people you might actually bump into

in a small Japanese town, like the American wife of a store owner who needs

detailed placards on the walls of their shop to help her speak fluent Japanese

or the yakuza disposal site employees who are completely casual about their

career in crushing human bodies into pulp and retaining their skins.

What helped me to fall in love

with Gozu is that it's a film where

an everyman is placed within a world that's both very mundane and utterly

bizarre, and both sides are as strange as each other, where even the doubling

size of his meals at a hotel gains a reaction from him and us as a viewer of

surprise. Little details pull as much humour as the more twisted moments,

giving Gozu a greater effect.

Personal Opinion:

Gozu is one of Takashi

Miike's underrated and best films. Not because it's weird for the sake of

weird, but because it makes both normalcy as weird as the bizarre,

transgressive material and the sides meet together to create something as

perplexing to follow as its ghoulishly funny, ending on a happy ending that's

surprisingly sweet despite the yucks that taken place beforehand.

|

| From http://sqd.ru/files/g/ozu6.jpg |