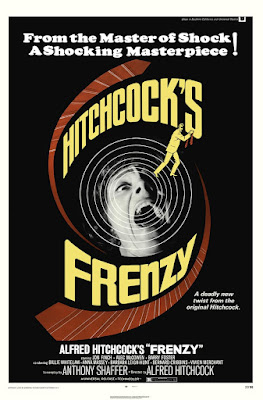

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Anthony Shaffer

Based on Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square by Arthur La Bern

Cast: Jon Finch as Richard Blaney,

Alec McCowen as Chief Inspector Timothy Oxford, Barry Foster as Bob Rusk, Billie

Whitelaw as Hetty Porter, Anna Massey as Babs Milligan, Barbara Leigh-Hunt as

Brenda Blaney, Bernard Cribbins as Felix Forsythe, Vivien Merchant as Mrs.

Oxford, Michael Bates as Sergeant Spearman, Jean Marsh as Monica Barling, Clive

Swift as Johnny Porter, Madge Ryan as Mrs Davison, Elsie Randolph as Gladys, John

Boxer as Sir George

Canon Fodder

One of the last Alfred Hitchcock films, Frenzy stood out in his career with its impact making sense in context. By the seventies, Hitchcock had not made that many films since 1964 next to his prolific golden period from 1950 onwards, having struggled with his attempt to be an independent producer of his own work in the late forties and failing. His golden era, which gave us films like The Trouble with Harry (1955) to Psycho (1960), and did not have producer David O. Selznick involved as his forties career, for good and for bad, ended in the mid-sixties with him considered a huge unreliability. Hitchcock is a controversial figure for how he depicts women, his obsession with the "Hitchcock Blonde", and for me, it is everything with actress Tippi Hedren where I agree is the uncomfortable moment where he crossed a line. I cannot defend what happened with how he treated her on both films they worked on, but it also clearly crossed a line to even alienate those close to him and studio executives at Universal. The first film, The Birds (1963), was a box office success, if one which would have got him cancelled for the story of what happened with Hedren on set, but Marnie (1964) was not, and was the straw which broke the camel's back.

Frenzy's genesis likely comes from a project Universal confiscated from him, Kaleidoscope, a proto-Frenzy which was meant to be very explicit, sexually and in terms of violence, influenced by the like of Blow Out (1966) by Michelangelo Antonioni, to be shot with handheld cameras, natural light and location shooting. Personally the films which we did get after Marnie have their virtues if their problems are felt in their sluggish paces and having his creative power pulled from - Torn Curtain (1966), as Hitchcock has to put up with Paul Newman, as someone who hated the method acting style, has this issue as does Topaz (1969) - but Frenzy feels alive and still disturbing decades later. As a lower budget film shot in his homeland, as someone who was an old man by that point, he nonetheless got carte blanche to make a film which does not feel antiquated and with a sick humoured tone. Frenzy is the most explicit and adult film in his career, but this tale of a serial "neck tie murderer" killing women in London, despite it being lurid subject matter explicitly invoking rape and strangulation of these victims, is more startling because of its sense of humour contrasting this premise. When members of the police trying to deal with the case in a pub talk of the psychology of said killer, only to say having a sex murderer is good for English tourism, it emphasises the gleeful misanthropy felt fully throughout this film.

This will make some very uncomfortable for Frenzy, but in context, what has aged is ye old seventies London, and that feels like a time capsule to what locations we still have, starting with the opening by London Bridge and the Thames, only to undercut them with from the get-go with a public gathering interrupted by a female corpse floating in the river. The set up is the traditional Hitchcock wrong man scenario, in which the obvious red herring is Richard Blaney (Jon Finch), a former lieutenant of the air force reduced to a bar man fired for drinking on the job and forced to sleep at a Salvation Army hall when he has no money. It is very obvious and not hidden who the killer is, his friend and market fruit & vegetables seller Bob Rusk (Barry Foster), with the reveal a disturbing one which places Richard as a suspect, as it involves the murder of his ex-wife. To the film's credit, and why it's more salacious and sick humoured aspects work rather than feel inappropriate, is that when it is about the awfulness of these murders of women, they are meant to lead to revulsion, whilst the humour is felt in terms of how, as throughout Hitchcock's career, he has an obsession with this twisted side of the human consciousness, its obsession with crime and murder, where the humour is the relieving puncture of the tension.

The parallel plot is Chief Inspector Timothy Oxford (Alec McCowen) who is investigating the murders, and this is where the humour especially comes in, that his wife is also into cuisine cooking. It is surprising in context to how explicit and grim the film is, the sole one to be fully able to in Alfred Hitchcock's career than imply such themes, and yet this is one of the most distinct parts of this entire film, funnier when you are aware of his and wife (and important collaborator) Alma Hitchcock's love for cooking and cuisine, thus presenting us with dishes of a solitary quail on a plate with a few measly grapes, or a soup full of fishes heads, when all Oxford wants is an English breakfast. There is still the style of older Hitchcock films here too, which was only briefly seen in both Torn Curtain and Topaz, the flashes of his deft hands when a tragic death of a main character is perfectly depicted with the camera in one take leaving the environment back out onto the street, without needing to show us what we know is going to happen. There is also the set piece with a truck full of Lincolnshire tates (potatoes) which mines tension against the sick humour from the act of disposing a corpse, including rigor mortis and a neck tie pin that needs to be retrieved, all despite the figure involved being a complete monster now in peril. You should not be laughing either yet the farcical nature of such a gristly scenario is felt to ease the tensions.

What is also felt particularly that here too, despite the character of Oxford who happens to be the one person, including the wisdom of his wife, to think, is Hitchcock's long standing paranoia and distrust of the police and the law, especially when people are quick to put the kicks in Richard as witnesses, like the male bar manager who fired him. Throughout Hitchcock's career, including adapting a real life case of a man put to trial as an innocent The Wrong Man (1956), ever since he was put in a jail cell as a child which created his long standing fear of authority, Hitchcock has always shown the frailty of the system. Even the murderers in his career do their acts for petty grievances, or here have compulsive sexual dominance obsessions but look like nice blokes who sincerely love their mothers, and that is probably the most misanthropic aspect of Frenzy as well as Hitchcock's career. Barring his forties work where he decided to fight real fascists by pitting his characters against reel ones, his work as always had this, and whilst the adult content here is strong, the more potent aspects are the gullibility of law and the matter-of-factness of such disturbing crimes taking place in a world where you could still smoke in pubs. The air of downbeat grungy London, like a lot of more lurid genre films from this era, makes its way here too, adding to the macabre nature, emphasising all these traits and adding to the atmosphere, and whilst I would argue his final film Family Plot (1976) is deeply underrated, I see why Frenzy is a late era Alfred Hitchcock film that is held in high regard for good reason.

No comments:

Post a Comment