|

| From https://image.tmdb.org/t/p/w300_and_h450_ bestv2/3CmVcJhPYWcJCue3fs38SaiFyoi.jpg |

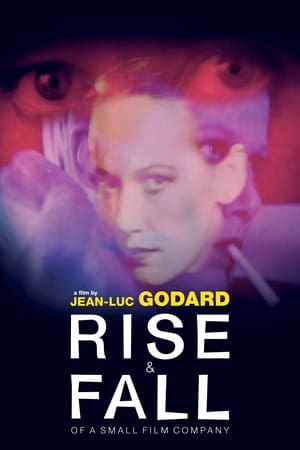

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Screenplay: Jean-Luc Godard

Meant to be based on the novel The

Soft Centre by James Hadley Chase

Cast: Jean-Pierre Léaud as

Gaspard Bazin; Jean-Pierre Mocky as Jean Almereyda; Marie Valera as Eurydice

Synopsis: The state of cinema by way of an adaptation of a James Hadley Chase crime novel,

originally produced for the crime story series Série noire in France. Where producer Jean Almereyda (Jean-Pierre Mocky), once a matinee idol

and major producer, is now reduced to TV movies and dogged by a case of stolen

money from his past. All whilst Gaspard Bazin (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a director who now, after acclaim, spends his

time in an obsessive ritual for casting extras that eats up their budgets,

finds Almereyda's wife Eurydice (Marie

Valera) a potential creative source when she desires to be an actress.

Synopsis: The state of cinema by way of an adaptation of a James Hadley Chase crime novel,

originally produced for the crime story series Série noire in France. Where producer Jean Almereyda (Jean-Pierre Mocky), once a matinee idol

and major producer, is now reduced to TV movies and dogged by a case of stolen

money from his past. All whilst Gaspard Bazin (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a director who now, after acclaim, spends his

time in an obsessive ritual for casting extras that eats up their budgets,

finds Almereyda's wife Eurydice (Marie

Valera) a potential creative source when she desires to be an actress.

It's strange we can uncover lost

films by Jean-Luc Godard, one of the

biggest names in all cinema, but we can forget that even after ten years

obscurer films in a director's filmography can be neglected absentmindedly.

There is, of course, when new blood in the fan base don't know common knowledge

that the older members do, something which can happen be it for horror fans to

art house aficionados, and in that case we need to provide that information or

doom ourselves to obscuring works of the past. Retrospectives are thankfully

more common too as are physical released, but there are cases, with a director

like Godard who made so much outside

of theatrical screenings, that once it was a lot more difficult to access this

material and a lot of it hasn't even been gotten around to until now. That even

a great American director can have material not available means that the Swiss

director, even if he is a legend in cinema, can have probably more as both

being a director who worked in a foreign language to English, made very

difficult work that contrasts his famous early sixties works immensely, and has

experiments in television and short work more rife than many other filmmakers

which always tend to be neglected with any auteur. So, yes, you have the clues

to why we trip over these obscurities like so.

Even in the theatrical corner of Godard's wing, where for many his debut Breathless (1960) is his most well

known film, there are productions neglected especially in the late eighties

when, returning with his second "debut" Every Man For Himself (1980) after his experimental era, which are

not available. Now which his Dziga-Vertov

Group films (mostly) available in high definition, even if many are some of

the most painful failures of his career, the Holy Grail alongside films like

the controversial Hail Mary (1985)

is his television work. Experiments like Rise

and Fall of A Small Film Company. From

a time where he was going to return back to experiments until the unforeseeable

day and was in-between various projects, a year before his infamous Cannon Films production King Lear (1987). One very much not

taking his assignment with Série noire

as intended.

|

| From https://medias.unifrance.org/medias/252/193/180732/ format_page/rise-and-fall-of-a-small-film-company.jpg |

Rise and Fall, rather than the adaptation of a crime novel as likely intended, is that meeting place between the return to narrative cinema in the eighties and the video experiments that would lead him to his career in the current day. The noticeable limitations - the TV screen ration, the limited aesthetic, the video sheen and digital text captions - are things that would undermine another director, but are like providing Godard with new tools to work with. He's someone, know to use VHS rips of old films on purpose still to this day, completely polymorphous when it comes to technology, already working on television productions in the seventies and, in the 2010s in his older statesman position, having his own 3D camera built by scratch and making a 3D feature in Goodbye to Language (2014). Here though he's still working with a plot, around one which contrary to his famous quote does have a beginning, middle and end in that order. The struggles of a TV movie company mid adaptation of James Hadley Chase's The Soft Centre, the novel Godard is meant to adapt, which he weaves his state of unrest cultural critiques in the midst of through the tired producer Jean-Pierre Mocky (Jean Almereyda), and the frankly deranged director Gaspard Bazin (Jean-Pierre Léaud).

Léaud, meeting back with Godard

and thus evoking his many moments in the latter's work, could if you cheated a

little be the exact character he would later play in Olivier Assayas' Irma Vep

(1996). The same director hired to remake Les Vampires (1915-16) in that film, who decided to cast Maggie

Cheung, once before with an entirely different name stuck in these wilderness

years in the late eighties, his obsessive ritual with the extras of having them

move through rooms in a conveyor belt,

quoting at one point the same passage contracted together between them, as much

him attempting to find his creative sanity as a madness. He's less irritated by

being stuck making television work, but as he confesses (and shows Godard biting the hand financing this

feature) wishing he was adapting Dashiell

Hammett instead. In a world where he and his producer sit in front of a

television showing a fire, rather than a real one, to stay warm, the world has

become stranger than the sixties they made their fames in. It's not an absurd

comparison either between films as, whilst the ending of this suggests a happy

ending for Léaud's character, the

film making world is so different from France's before, where his arcane ritual

with the casting is chewing up money for a company who can't even get a TV

movie off the ground and shown.

|

| From https://i.ytimg.com/vi/069Xaf__6nM/maxresdefault.jpg |

Admittedly Godard's criticisms of the state of cinema and life, as he's been doing them since the sixties and hasn't stopped since, could dangerously fall into shouting into the wind, worse a man trying to joust windmills thinking they're dragons. (Even if that's the case for some now, I'd at least want to picture him as cinema's Prospero, in his magical tower in Switzerland creating his cinematic incantations, or like his character Professor Pluggy in King Lear with patch-cord dreadlocks in his hair). What doesn't allow this to be the case is that, generally, his philosophical concerns are not only enlightening but constantly evolving over time, the ones of yore still relevant to the current day or time capsules to new problems per era. Here, ironically when he was asked to make this TV film, he's practically spiting the producers by having the pair of Bazin and Almereyda as doomed figures of the past floundering even in commercial television. Their lives are small scale, the television budget and style of Rise and Fall... helping this. It is too rye to be an out-and-out comedy, but humour is to be found especially in characters like the accountant, who in deadpan just doing his job hands out paltry earnings to the extras discounting their social security. Or Léaud playing up his character's out-of-control behaviour, be it interrupting a phone call between a potential actress with acute abruptness, brought at what she suspiciously suspected to be erotic when asked to bring a bikini alongside her, or breaking into a Woody Woodpecker impression.

Godard's also one of the few directors able to get away with casting

himself as the wise sage. Much of it, by this time, is because Godard was such

an iconic name it was impossible to get around this, common in narrating his

own films since the sixties and having a reputation as a figure outside of

cinema, making his work (usually dialectic anyway) completely attached to him. Rise and Fall... offers him playing a

character as himself, amusingly (as I want to picture it) living in Reykjavik in

Iceland because he had to witness the greatest chess game being played there,

here appearing to find a deal back in the left for him with a (fictional?)

producer and Romy Schneider. Thus his

scene also turns to an appropriate melancholic air about the period, when both

said producer is dead and Schneider,

in real life, passed in 1982. When that comes to pass it becomes one of the

film's most meaningful scenes, more so because Godard is playing himself interacting with a fictional creation of

his, two old pros lamenting their careers in cinema being affected by the

change in tide and left adrift within it. Even if Godard would become more and more a legendary filmmaker who made

films to the current day, he's eventually drift far from narrative cinema into

experimental features entirely, all bolstered by the reputation he developed

allowing him to leave mainstream cinema behind.

| From http://media.flix.gr.s3.amazonaws.com/cache/ bf/17/bf17279cd12d76950b8214b952776420.jpg |

His critiques are matched by a willingness to play with the form of film a way few would. The limitations, the flaws, of this television work are devices for him to exploit, superimposition to the hair-raising use of slow motion on a female extra's emotions mid-performance. He even deliberately has the sound abruptly halt as if the film's failed, followed by a technical difficulties screen, for a joke. Musically he picks interesting pieces like from Leonard Cohen to Janice Joplin, the latter's famous rendition of Mercedes Benz amusingly used on a moving computer square with the technical screen colourbars. The marriage between the two sides is like a very underrated theatrical feature Godard made within this era, Detective (1985) with Johnny Hallyday and Nathalie Baye, a small scale crime narrative confined to one hotel, perfect for Godard's experimentation as well as providing an actual story. Rise and Fall... still tells an interesting tale - for Jean-Pierre Léaud's Bazin, a spark of life is found in his producer's wife Eurydice (Marie Valera), who he compares to actress Dita Parlo known for films like Jean Renoir's Grand Illusion (1937). Theirs is not a romantic or sexual relationship, instead Bazin finding artistic clarity as, testing her, she is one of the only people when giving an old painting will not point out all the figures within it but say the characters are actually the most important themes of said painting. Sadly, apt for a small scale crime drama about a little company, it's the producer's shady past with stolen money that does them in.

Abstract Spectrum: Avant-Garde/Diegetic

Abstract Rating (High/Medium/Low/None): Low

Personal Opinion:

Hopefully, restored and premiering

at the 2017 Locarno Film Festival,

the reappearance of Rise and Fall of a

Small Film Company is not restricted from public access beyond being temporally

streamable on MUBI. If Godard's Dziga Vertov years can be accessed, as difficult and un-cinematic

in his career's work as you can get, an uncovered gem like this can have

appeal. If anything it hopefully leads closer to the vast television and video

work in his catalogue finally appearing in wider access.

|

| From https://assets.mubi.com/images/notebook/post_ images/26139/images-w1400.png?1530550709 |

No comments:

Post a Comment