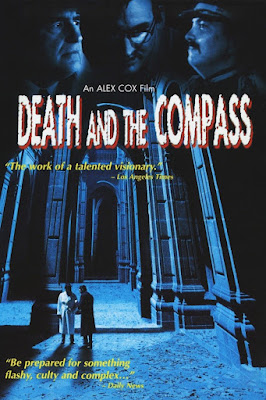

Director: Alex Cox

Screenplay: Alex Cox

Based on the short

story by Jorge Luis Borges

Cast: Peter Boyle as Erik Lonnrot; Miguel Sandoval

as Treviranus; Christopher Eccleston as Alonso Zunz; Zaide Silvia Gutiérrez as Ms.

Espinoza; Pedro Armendáriz Jr. as Blot; Alonso Echánove as Novalis; Eduardo

López Rojas as Finnegan; Alex Cox as Commander Borges

Canon Fodder

Let's just say I'm looking for a more rabbinical explanation.

[Major Spoilers]

Death and the Company, first of all, has a very unconventional production history which influences the final theatrical release. That, originally, the cult filmmaker Alex Cox was commissioned as part of a series of adaptations of the work of Argentinean author Jorge Luis Borges to adapt Death and the Compass for an hour long story, part of a series which was shown on the BBC in Britain called Cuentos de Borges (1992). This show, which is obscure, is fascinating as a concept for a series, especially as notes reference an episode with Antonio Banderas and another called El Sur, an episode by acclaimed Spanish filmmaker Carlos Saura.

Alex Cox's episode however would be expanded to feature length with Japanese co-funding, leaving Death and the Compass having a curious expanded nature to consider alongside being canonically part of his filmography as a big title as a result. The really interesting thing about this, in mind to the source material and how faithful this is in places, is that Borges' source material is practically a skeleton. A compelling little short story but it is a short work, more an outline to a longer piece, but itself masterful. Borges, in what I have read, is a truly unique voice. His is the ability to start with pulp or genre beginnings in his work, or sometimes from one idea, this effectively a pastiche of detective narratives, and enter abstract/fantastical logic able to use the ability of the written word to have no limits. The Garden of Forking Paths is a spy story where the protagonist accidentally encounters the notion of infinite multiple directions, multiple dimensions, to every movement or act of his which fork off in different directions. One narrative in a short story is a man dreaming his form. Another a library of infinite books which gets into details like a cult surrounding finding one specific book in an infinitely expanding space of them. Another was a man writing a copy of Don Quixote without reading the original book to find its meaning. Borges' literature is unique and emphasises what the written word can do that other mediums cannot.

Death and the Compass is pretty simple, but I have to immediately spoil the ending to get an idea of what the point here is. That Detective Erik Lonnrot, played by Peter Boyle, in the short story and the adaption finds himself at a murder scene of a Jewish mystical scholar in a hotel room, finding a typed piece of paper saying "The first letter of the name has been uttered", and believes this is all connected to a Jewish mysticism alongside other murders and events that follow on. They are proven a trap, his folly to over think the obvious and fall into a deception of a larger meaning to a series of crimes than what is presumed. He is trapped in a liberty designed for him by his nemesis, Red Scharlach, played by Christopher Eccleston, as much improvised from an accident to get revenge on Lonnrot.

Alex Cox himself is a fascinating figure to come into this. Repo Man (1984) is his most famous film, and in a combination of bad luck and having to work around what films he could make, which he has been able too, his is an eclectic and idiosyncratic world of films that are unpredictable. Compass immediately stands out before the film even begins with an eerie carnival piano with industrial groans in the first moments of the score, the music by Pray for Rain going to make itself known and a pronounced part of the film adaption's character. Death and the Compass is very faithful to the source, actually adding content, and Cox as the screenwriter is making this material his own as much as a faithful Borges adaption.

It is a fascinatingly odd pastiche of a pulp crime narrative, expanded even in the short story into an extended template such as The Garden of Forking Paths, here a Kabbalistic related string of murders, of rabbis and Kabbalah researchers, which worms into Detective Lonnrot's obsession just from a piece of paper in a typewriter at a murder scene. The most interesting thing about the adaptation, alongside how Cox adds his own unique flesh to the original text, is how this version feels unlike the original. The short story was penned in 1942 and feels a work of the era, of Argentina (or an unknown melting pot fed from reality) as a diverse environment of people and religions, whilst this film's world is openly (shot in Mexico) a dystopia in the future. Some of it is in danger of being gauche - how the three leads are colour coded in bright primary colours, Lonnrot in blue, Red Scharlach in his namesake red, the conservative and ultimately gutless Treviranus (Miguel Sandoval) in yellow. Here in Cox's world, including in a theatrical cut a bank heist with a prowling one take camera movement, and a cameo for himself as a blind detective, there is a dystrophic feel of a rundown city, of political corruption, a civil war brewing and the police (under Treviranus) becoming more of a thug unit.

This is apt, despite not being needed in the source text, knowing Borges would only pen one film screenplay in his career, co-writing the Argentinean one-off Invasión (1969), a work set in pulp mystery structure that, alongside feeling inside a dystopia, was suppressed by the Argentine dictatorship of 1976–1983, and effectively lost until its rediscover decades later. If anything, Alex Cox's work in this is entirely in mind of adding his own flavour to the production, even changing the text at times into a new personality. Peter Boyle's Lonnrot is a mystically interested figure here, practicing Buddhism and fascinated by religion, a figure in danger of his own persona being an ego and his trap, such as insisting on using a non-regular police car in favour of one which has to be constantly repaired. Treviranus, in the adding footage shot post-narrative as an old official, was barely a character in the source story; here he is not a likable character at all, clearly corrupt or problematic as a member of the police force, but when the narrative is shown was at least right in Lonnrot falling for his own trap. Red Scharlach is not really fleshed out, looking here like a cartoon strip villian, but in the source material, he was just meant as a stock antagonist. Christopher Eccleston gets a lot more from other aspects of his role which are very obvious in who is playing who. It is interesting to known Eccleston, who many will know through the first Doctor Who reboot in 2005 and the likes of Shallow Grave (1994), had a brief moment of these Alex Cox films, getting a lot more to work with in Revengers Tragedy (2002), an adaptation of a Jacobean revenge tale from the seventeenth century, set in the future, where he got to flex his acting muscles but also play a scene of acting deranged talking to his wife's skull.

Technically the film is fascinating, though its origins as a production rebuilt to be longer does present a curious touch. I think out of all its aspects, the one which might prove an issue for many, depending on how its watched, is the sound design, which intertwining the great music from Pray for Rain with the dialogue and sound effects is a chaotic mix at moments. It manages, without falling off the rails, to be a chaotic film in tone in many ways yet adapt the source material. Treviranus' scenes in the future reflecting back could be excised but even they add to the character of a melancholy to the scenario from the least expected source. The long takes with the camera are impressive, especially as Cox fleshes out this dystopian version of the world of pure chaos, where autopsies are performed in the middle of the police station entranceway, and that the opening bank heist, set at a foundry to dispose of old money, is a grimy industrial labyrinth for the camera to weave through. The sense of the flamboyant even is to be found in how phone calls are depicted, superimposing shots within shots or even having the scene shot in darkness, only to illuminate a set in the background with the other person in the phone call involved.

The resulting film is a fascinating production. It is unique even next to the original text, which is an admirable virtue for Death and the Compass. It's appeal will entirely depend on the viewer's reaction to the narrative - where even if you have read this far and had the spoilers, the journey and the meaning were the most important aspect for Borges as it was for Cox, entering a sombre conclusion here in a haunting mansion location. It reaches a profoundness aimed for that, whilst very different, does evoke the messy production that was The Winner (1996), a film effectively disowned by Alex Cox due to tampering, but following in its own idiosyncratic direction with Las Vegas literally being turned off in the end, here the discussion of the most perfect labyrinth and past lives, with more dialogue than the source text added by Cox's script, leaves on a spiritually heightened mark.