a.k.a. Gushing Prayer: A 15-Year-Old Prostitute

Director: Masao Adachi (with

Haruhiko Arai)

Screenplay: Masao Adachi

Cast: Aki Sasaki as Yasuko; Hiroshi

Saitô as Kôichi; Makiko Kim as Yôko; Yûji Aoki as Bill; Shigenori Noda as Arai

An Abstract Candidate

The best way to describe Gushing Prayer would be to attempt to explain the film to someone who isn't a cineaste, with a lot of explanation having to be made first. First, you have to explain that, whilst an erotic film usually evokes softcore titillation or in some cases a drama, one exception to that rule was the Japanese "pink" movement where, for every film which was made up into the current day entirely for the sake of titillation, there were exceptions. Especially in the late sixties and seventies, as long as you kept under the low budgets and still had sex, you could make a film about any subject and structure. Adding to this tale would be to talk of Masao Adachi, a screenwriter and filmmaker who, working within the pinku genre with inherently political and unconventional structure, would eventually stop making films just at the time Gushing Prayer was created, joining the communist militant group the Japanese Red Army, and reside in Lebanon for decades until being arrested for passport violations in the 2000s. That this tale ends with Adachi being released from jail, making another film in 2007 (Prisoner / Terrorist) and working onwards, really emphasises both the idiosyncratic context to the film beyond sex and that Gushing Prayer itself is going to be as unconventional.

With George Bataille quoted before coitus and echoes added to voices in certain scenes to add a disconnected mood, this is pinku but with very different aims. Do not come to Gushing Prayer for sex but late sixties into the seventies political avant-garde or you will be sorely disappointed. This comes to sex as a subject for its characters to have to grapple with, four lost teenagers (two boys and two girls) trying to "beat sex", trying to escape their bodies and their sexualities to become something more when the lead among them, fifteen year old schoolgirl Yasuko (Aki Sasaki) has had sex beforehand with her middle age teacher and is expecting child. What this leads to is the quartet trying to overcome sensuality, effectively guilting Yasuko into being a paid prostitute for feeling something with her teacher.

With tanks on parade in the street, the film feels of a tense political time in Japan, the film the penultimate one in the filmmaker's career in his first arch, before The Red Army / PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), an overtly political piece before his complete separation from the art form for decades. Most porn films, to be blunt, do not have echoing voiceovers on a street taking of being unable to beat sex, and from its female voiceover of various ways an 18-19 year old girl committed suicide to the acoustic guitar score, Gushing Prayer does contrast the genre it is in, even in mind to said genre for the films meant to be erotic having a history of unpredictable and inventive productions. Even its habit, as a monochrome film, to switch to colour is used in provocative ways even if the film has a lot of nudity and sex emphasised by it too. When a son shows his friends his mother having sex in the bedroom to ask whether it is real, even if it is evoking titillation in the sharp turn to warm (reddish) colour, it does provoke a great deal in the context this is happening within when it's a character, quite an unlikable figure but one clearly trapped in a youthful despair, to show his mother in front of his friends having sex and all the baggage that involves. That the film is as well about teenagers rather than adults, despite a history as well in Western cinema of adults playing teenage character who are seen naked and eroticised in even comedies, adds an uncomfortable weight potentially for viewers too.

Honestly, the film itself feels alien in the modern day, an unknowable aspect to its tone and attitude which I can appreciate but in this case as well is in clear danger, despite being only under eighty minutes, of missing a point at all for a viewer, neither the pinku film about eroticism, and feeling of its time in terms of a rebellious avant-garde film, one which is severely limited in its choice of subject and may have lost meaning. Whether a good thing or one Masao Adachi was right to make, this is a film now you have to view with a generation where the idea of youths being this hopeless politically but wishing effectively for either permanently chastity or total mastery on a transcendental level, in a film grounded in its bleak Japanese urban streets, contrasts a world where many forms of eroticisms even merely imagined or faked are prolific, and do not even need other people involved.

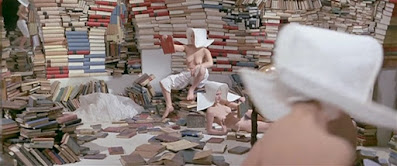

What grasps to me however, and will still connect to any viewer, is Yasuko, a figure who you are clearly sympathetic to. Her misanthropic peers, who wish to overcome sex and did not like the fact she broke their rule, are still alienated teenagers trying to grasp at something, refusing a basic part of their world and finding themselves unable to escape it. As the figure in among them who is the centre, Yasuko is a figure who resonates still decades later as a lost figure, able to briefly have a moment of joy, the colour footage returning for her to briefly play in her own daydreams naked as a nymph in an apartment, but the coldness of the world around her eventually crunches down. Deciding to turn the gas on in an oven is the sole option, and the colour comes back to haunt the viewer with blood in a toilet bowl.

It is a difficult film, all whilst never presenting a difficult aesthetic style, but still being a stark and confrontation piece in its tone and presentation. Merely that, with its mind on such a bleak tone and alienating in its genre tropes, Gushing Prayer is difficult to work with. Still with reward, but also a curiosity as a result in its genre and the avant-garde films made at the time. Knowing Masao Adachi was following on, as much as a screenwriter for the likes of Kôji Wakamatsu, on similar pinku films which challenged and rattled against their own genres, not films held as erotic but difficult avant-garde films, make this an interesting glance at them all.

Abstract Spectrum: Philosophical/Stark

Abstract Rating (High/Medium/Low/None): None