|

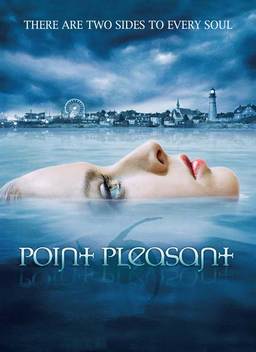

| From https://images2.static-bluray.com/ products/20/7462_1_front.jpg |

Creator: John McLaughlin and Marti Noxon

Cast: Elisabeth Harnois as Christina

Nickson; Grant Show as Lucas Boyd; Sam Page as Jesse Parker; Aubrey Dollar as Judy

Kramer; Dina Meyer as Amber Hargrove; Cameron

Richardson as Paula Hargrove; Clare Carey as Sarah Parker; Brent Weber as Terry

Burke; Susan Walters as Meg Kramer 13 episodes; Richard Burgi as Ben Kramer; Alex

Carter as Sheriff Logan Parker; Ned Schmidtke as Father Matthew; John Diehl as

David Burke; Adam Busch as Wes; Marcus Coloma as Father Tomas; Elizabeth Ann

Bennett as Holly

Obscurities, Oddities and One-Offs

The Omen: The New Jersey Shore

Years? Call this the result of listening to a podcast about cancelled tv

series, Cancelled Too Soon, but I

have gone out watch the material they have covered, and usually covered it on

this blog alongside my own oddities, all in spite of the fact that, beyond

anime and certain significant titles, my interest in television is virtually nonexistent.

I gave up television just for watching DVDs (and streaming) about ten years ago

out of disinterest in the product and being sick of adverts. In many ways,

seeing the style and tone of a show like Point

Pleasant, which I once grew up with, is better now in terms of being able

to judge the material when it isn't saturated in my everyday life and can be a

different experience from the rest of what I watch. Stepping out of my comfort

zone is worthwhile, especially when this thirteen episode series, from

co-writer of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Marti Noxon on board, is a teen soap

opera where the female lead is the Antichrist immediately tickled me pink as a

premise.

The Omen: The New Jersey Shore

Years? Call this the result of listening to a podcast about cancelled tv

series, Cancelled Too Soon, but I

have gone out watch the material they have covered, and usually covered it on

this blog alongside my own oddities, all in spite of the fact that, beyond

anime and certain significant titles, my interest in television is virtually nonexistent.

I gave up television just for watching DVDs (and streaming) about ten years ago

out of disinterest in the product and being sick of adverts. In many ways,

seeing the style and tone of a show like Point

Pleasant, which I once grew up with, is better now in terms of being able

to judge the material when it isn't saturated in my everyday life and can be a

different experience from the rest of what I watch. Stepping out of my comfort

zone is worthwhile, especially when this thirteen episode series, from

co-writer of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Marti Noxon on board, is a teen soap

opera where the female lead is the Antichrist immediately tickled me pink as a

premise.

She washes up at Point Pleasant and goes by the name of Christina

Nickson (Elisabeth Harnois), daughter

of Satan and a human woman as established immediately. Caught between his

minions, mainly former human Lucas Boyd (Grant

Show) trying to egg her on to kick-start the Apocalypse, and the deeply

divided but kind Kramer family who keep her humanity, the melodrama intermingles

with the religious horror (as she unwillingly draws out peoples' worst sides in

the first few episodes), but also tempers it in its own unique bombast as her

state of mind gets rolled about over the episodes.

The first thing that comes to

mind now, with time to reflect on the series, is the Twilight franchise, which for all the understandable criticisms was

enjoyable for the first film, all because it retold horror genre tropes through

this type of intimate melodrama about characters first; alongside the

increasing issues with the gender politics, the death kneel for me that it

became obsessed in the later films with the scourge of mainstream cinema, lore

and CGI ladled fight scenes with the moments of interesting dynamic, of a

romantic triangle between a mortal woman with a vampire and a werewolf,

dwindled out more and more. Point

Pleasant dangerously veered to this near its finale, more intrigued by the

religious horror we have seen in a lot of work before and after, but never became

overcome by it thankfully.

Again, when you've purposely

isolated yourself off this type of mainstream American TV, as I did, it's nice

to occasionally watch a work like this that, slick and conventional, feels like

a change of pace rather than drilled into me as a constant prescience. There's

little that has dated baring the occasional CGI (evil black birds in

particular), not feeling like the early 2000s in frosted tops in the hair or a

pop punk/post-nu metal soundtrack, instead set in a quiet beach town whose residents

are mild manned but start to become enveloped in a less transgressive version

of Peyton Place (1957). Whether they

are mild mannered - Sarah (Clare Carey),

church devotee and mother of lifeguard Jesse who rescues Christie - or from

soap opera - her sceptical, angry and easily jealous cop husband Sheriff Logan

Parker (Alex Carter), or friend and

notorious man chaser divorcee Amber Hargrove (Dina Meyer) - or from teen drama - the aforementioned Jesse (Samuel Page), who with Christie has a

won't-they-will-they crush or the many frequently shirtless young men in the

cast - there's enough to work with in stories. It's to a virtue for all its

macabre tone, even getting Danny Elfman

to compose the main theme, that it's still a melodrama at heart that is

timeless to any era.

It actually, unintentionally, exposes

how in terms of Christian lore as is interpreted by popular culture how

pointless and misguided the plans of literal demons are. Destroying the Earth

here is actually a waste of resources the longer you listen to the likes of

Boyd, even when Grant Show steals

scenes like an evil cad, when a more pragmatic and practical goal (when Earth

allows, for every good person, many evil ones too) would be more worthwhile,

such as just pushing Christie to a hierarchy of power where Satan would get

more resources for his side. Even the one attempt at nuisance, to dispose the

failed experiment of mankind, is just exposing how Western pop entertainment is

severely falling behind the likes of Eastern pop entertainment where even a villain

in a children's show had actually sound arguments to their ideas.

In reality, and why I am actually

glad the series ended at one season as this became more increasingly relied

upon, the more absurd aspect of the entire series isn't the soap opera but the

religious horror, especially when it becomes more increasingly relied upon, and

the weakest parts are those which are entirely plot lines from a tedious horror

film from around this era. A lot of what

comes off as camp, even when it's still entertaining because of the melodrama,

is entirely the apocalyptic material, 666 literally tattooed on Christine's eye

and enough clichés to decorate your walls with appearing, including for all I

know ones from the Italian Satanic panic rip off films made in the seventies.

If I ever properly read the Bible, beyond going to a school as a child the

vicar frequently visited and the one time I read Revelations for some reason,

I'll gladly wager to you the reader that, for all the contradictory and problematic

scripture, the religion that gestated Dante's

Divine Comedy, and William Blake's poetry and art, is both

far more morally and intellectually stimulating than the usual tropes of devils

disturbing the priesthood, to batardise a Black

Sabbath song title, whilst being underused to a detriment for great

entertainment. So much so, and why Point

Pleasant won me over, that the earnest if over-the-top melodrama managed to

refresh the kind of clichés I'd eye roll at and add spark to them.

|

| From https://cdn-static.sidereel.com/episodes/111061/webtv_featured/127232.jpg |

This is more so having grown up with a lot of generic satanic horror in the late nineties to early 2000s, such as when Arnold Schwarzenegger fought Satan in Arnold Schwarzenegger, giving something like this from much later and after its co-creator created such a major nineties horror series beforehand more credit for just taking a risky gamble. (And that's in knowledge, from the likes of American Gothic (1995-6), that shows like this come from ten years earlier that follow this genre blending premise and are now of great interest to me). It makes the material much more rewarding even if there's as much subterfuge and misdirects to spin episodes longer than logically there should, all due to teenage angst and inexplicable bog zombies cameos, to romantic rivalry or characters developing abrupt serial killer urges. Here, a priest discovering Christie's secret, only to get killed by a burning boat accident, is made compelling again when the boat's part of an annual boating festival, in an episode as concerned that Jessie's original girlfriend Paula (Cameron Richardson), daughter of Amber Hargrove, is jealous he's being wooed to Christine whilst said mother is eyeing up Ben Kramer (Richard Burgi), a doctor with skeletons in his own closet as well as a wife Meg Kramer (Susan Walters) who has had mental illness since the loss of her older daughter Isabelle, but is also revealed later in the series to have actual supernatural aspects behind this. That, over forty four minutes per episode, alongside being tongue twister of a sentence to read, just gives you an example of how much is crammed into just one early episode. It is such a breath of relief from po-faced but average religious horror I've grown up with, to watch this instead; many which barely get anywhere, despite being on a global scale, are dwarfed by a work that focuses on one town but has so many stories, subplots and character interactions intertwining with each other.

It also means my growing

admiration with melodrama is with good reason - once housed with "women's

pictures" in cinema, like those made by Douglas Sirk, its arguably a vibrant, layered art where even

something more trashier here helps get a lot of nuisance from this premise. Even

if I've found the evil side's plans utterly pointless and one dimensional, the

melodrama makes sure there is something else to add engagement to these

characters. It allows good performances at least. Dina Meyer, most well known for Starship Troopers (1997) and a lot of television has always been

good, as a woman who sides with Boyd to seduce Dr. Kramer only for her humanity

especially to her friend Meg Kramer to become a greater factor, Susan Walters as Mrs. Kramer herself

giving a potentially trite character (mental health issues, actually with supernatural

gifts) more humility especially as the series progresses. And of course, Grant Show's Boyd is good, more so when

his back story shown in Episode 5 ("Last

Dance") casts more light on his previous life and leads to a new

character being introduced later on; set within the Great Depression for part

of its length, as Boyd recreates a

dance marathon in the current day town, Episode Five is arguably the best as,

whilst it has silly details like the aristocracy of old Point Pleasant

gleefully watching impoverished couples dance to near death, it adds to his

character when before he was one dimensional, despite Show's magnetism, and has a remake of Carrie (1978) with a blood shower and a disco ball of death that is

a plus for any television episode.

If there's any moment which feels

like Point Pleasant stretches

itself, it's at the climax. It does lean, as mentioned already, further into

the religious horror the further it goes, introducing a mirror to Christie's

Antichrist which is dramatically ironic for tragedy, but thankfully for all the

moments where the melodrama merely takes a backseat or is merely a catalyst for

the other half, such as a secret group of anti-Antichrist individuals not above

emotional blackmail for their sacred cause, there's plenty to still appreciate.

The final episode in particular, likely made with knowledge Point Pleasant was to be cancelled,

goes knee deep into a crazed family psychodrama, one slightly undernourished in

production but still literally with hell breaking loose as [PLOT SPOILER]

Christie turns full blown evil like an angry super powered teenager [PLOT

SPOILER ENDS], the dead brought back just to psychologically damage siblings

whilst someone complains about stale cookies. Even if you skipped that spoiler,

I can reveal that, whilst the show clearly wanted another season and a bigger

budget, Point Pleasant still got a

conclusion which is open ended, but of great importance, feels like a natural conclusion

most cancelled series wished they had. The issue of whether this series

would've dropped that great melodrama comes to mind, but what we got was

assured for this and thankfully ended on its best virtues.

It was a series I'm surprised

didn't last. It is, for all its quirks, the kind of PG-13 work with a bit of

sex (no nudity but a bit of hinted at facsimile alongside many shirtless guys)

and horror that, with its heightened emotion, should've gotten a fan base as well

as won me over decades later. Obviously, as well for me, it's probably for the

better it only lasted this long so any stagnation didn't corrupt its virtues,

but the mix if anything is the kind I wish took place more in Hollywood cinema.

Again, Twilight is evoked as that

should've been like this, with bigger production value, but squandered its best

in the first film for a convoluted, boring lore of action fantasy rather than

its original romantic love triangle as interpreted by Universal horror monsters. Pointedly as a criticism as, with a

female lead, Point Pleasant can so

be read as a metaphor for adolescence, the moral chasms she has to face as much

a character trying to find her morality whilst every other drama is an

exaggeration of real life issues soap operas use. Again, especially if Point Pleasant focused even more on its

community that just also happened to be a warring state between the forces of

good and evil, "The Omen: The Jersey Shore Years" despite being an

opening review joke was a perfect description of what it should've followed

fully and at times thankfully did.

|

| From http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_mpBGa4P5jUo/TSHsaixkAiI/ AAAAAAAAGE8/fzkDS-IPKzY/s1600/pointpleasant3.jpg |